Dr Nick Shepherd examines youth work statistics to explore the relationship between paid workers, their training, and the cultivation of volunteers in church ministry.

Statistics are sometimes helpful in highlighting the trends we need to respond to. In this reflection on the insightful statistics on Christian youth work by Youthscape I want to highlight two areas that need a nudge – our approach to ‘volunteers’ and our paradigm for ‘training’.

The survey is interestingly split 50/50 between volunteers and paid workers (Assuming the 9.1% other don’t class themselves as volunteers for good reason!) We know from elsewhere that the vast majority of the ‘workforce’ in Christian youth work are volunteers, especially in church contexts. In non-church contexts it appears that more paid work is visible. Again though it’s not far off 50/50. In recent years it feels that much has been done to promote full-time engagement in Christian youth work. Paid roles are directed towards working with young people themselves. I wonder then if this data suggests that this is the right focus. What if the real opportunity here is for paid roles to focus much more on developing volunteers?

No doubt many of the full-timers, or experienced volunteers, are doing this. However, this is not often an aspect of the roles we advertise or prioritise. This is not to suggest that such posts would have no contact with young people, nor be backed up by theological or professional training. Yet if we want to address the training and development needs the survey identifies, we have to think pragmatically about this being the best way to achieve this. What might this look like? Well, it doesn’t look like more people running more courses.

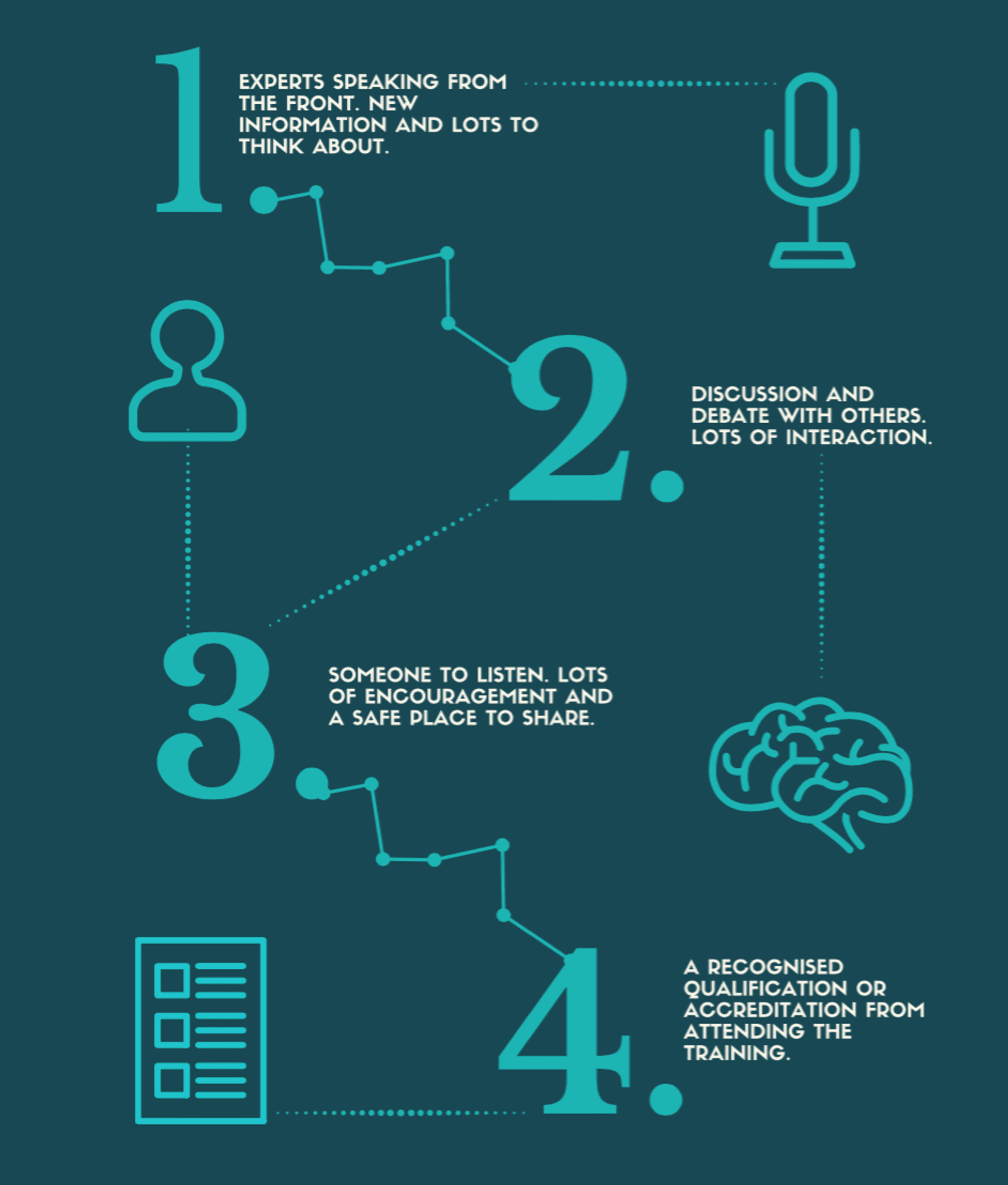

Accredited courses are at the bottom of the list, which is just as well since most people don’t have the time or funds for training anyway (45.9% no time, 31.7% no funds). Further, over a quarter think there is limited training of relevance as well. It’s interesting that 50.2% of respondents see ‘meeting other youth workers is as important as training’ and yet at the same time rank ‘experts speaking from the front’. However, the ranking of desired training in this survey exactly meets the model of ‘training’ that is now becoming more firmly established in continuing professional development contexts, what is called the 70:20:10 model for learning and development.

The 70:20:10 model is based on research by McCall, Lombardo and Eichinger at the Center for Creative Leadership, and published in 1996. They investigated how leaders learn and concluded that successful development came in the following proportions:

70% FROM WORKING ON TASKS OR PROBLEMS (experience)

20% FROM OTHER PEOPLE (good and bad examples!)

10% FROM TRAINING COURSES AND READING (formal and informal learning opportunities)

Like a lot of development models, it is not concrete, but it does offer a helpful way of simplifying a complicated topic and to recognise that our learning and development is shaped not just by formal training but to a larger extent by day-to-day experience. Flip the ‘desired training’ around, and it illustrates this well. People are not interested in accreditation – but are interested in developing. They are busy, they are doing stuff and they are (in my view) learning. Next then we have “Someone to listen. Lots of encouragement and a safe place to share” and “Discussion and debate with others. Lots of interaction”. This is our 20% zone of gathering people with shared problems and grounded insights. Finally we have the 10% cream – “Experts speaking from the front. New information and lots to think about”.

So here’s where my two thoughts combine: What if the focus for employed posts was directed towards the care and development of volunteers and the development of 70/20/10 training?

Might this lead to establishing more effective resources for people who clearly wish to engage in deeper understanding and sharper practice? The best accredited courses I know are already beginning to do this. That’s the trend we need to take further.